加

11/07/2022

History

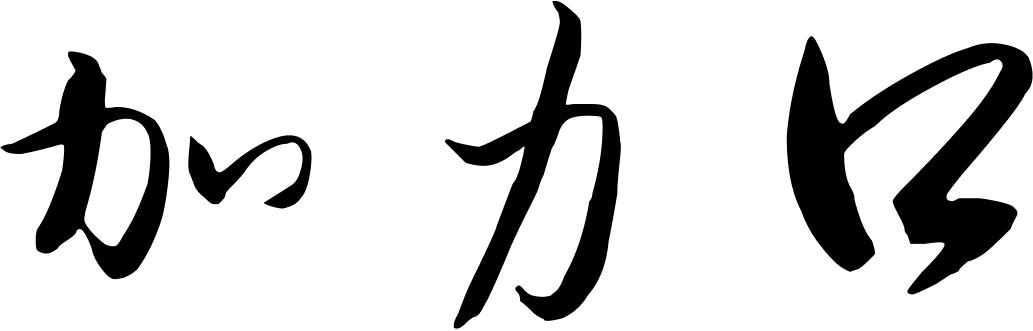

The Chinese character ‘加’ is translated to ‘add’ in English. It is made up of two separate Chinese characters. On the left side, there is ‘力’ which means ‘strength’ or ‘force’. Early glyphs resembled the shape of a Leisi, which was a plough used in agriculture. On the right side, there is ‘口’ which means ‘mouth’ or ‘entrance’, which it resembles (Fig. 1). According to Sun (2014), the meaning of addition comes from the work of continually digging the ground, combined with the sound of the mouth when using force.

Like many Chinese characters, ‘加’ has its origins in agriculture. As technology developed and popular Chinese culture shifted away from a farming-centric society, language evolved along with the changes across communities. The need for literal representation in written communication faded, and abstractions replaced them. Thus, the original meaning of ‘加’ was ‘to add strength’, however, today, the meaning has evolved to mean ‘to add’ in the general sense of increasing.

The romanization, or pinyin, of ‘加’ is ‘jiā’. There is a diacritic over the ‘a’ to indicate that it uses the first tone in Mandarin. Often in Chinese, two or three characters are combined to form different words. ‘加’ is used frequently – it is the 166th most common character in books, and 217th most common character in movies (Cai and Brysbaert 2010). For reference, there are over 50,000 Chinese characters in existence, however, an average educated Chinese person will know about 8,000 characters (BBC 2014).

The most common words in Chinese that use ‘加’ include ‘参加’ (cān jiā) which means ‘to participate’, ‘增加’ (zēng jiā) which means ‘to raise’, and ‘加油’ (jiā yóu) which literally means ‘add oil’, but is generally used as an encouragement, like ‘good luck’ or ‘don’t give up’. Because ‘jiā’ shares phonetic similarities to the English ‘ca-’ prefix or ‘ga’ sound, it is also used in the Chinese words for location names, such as Canada ‘加拿大’ (jiā ná dà), California ‘加州’ (jiā zhōu), Chicago ‘芝加哥’ (zhī jiā gē), Singapore ‘新加坡’ (xīn jiā pō) and Galatia ‘加拉太’ (jiā lā tài).

I picked this character because it is part of my Chinese name, 陈立加 (chén lì jiā). In China, it is common for siblings or family members in the same generation to share a character in their name. In my extended family, my cousins share the ‘立’ (lì) character. Because I am the only cousin who was born in Canada, my name is ‘立加’, which represents the ‘加’ in Canada.

小赖 The 小赖 (Xiao Lai) font is a simplified Chinese font that is based on the Japanese 瀬戸(Seto) font. The font name is also known as “Kose”, which is closer to the Japanese pronunciation. The original Japanese font was created by Seto Nozomi, of which version 6.20 was released in 2014. In March 2020, Max Yao released 內海 (Nai Kai) font, a traditional Chinese font based on Seto, which became popular in Taiwan and Hong Kong. However, as the font was still lacking simplified Chinese characters, in May 2020, the first commit was made to the Github repository for Xiao Lai, by 落霞孤鹜 (Luo Xia Gu Wu), also known as Github user “lxgw."

In Xiao Lai, the elements of ‘加’ work together to create a visual balance. For example, the upper horizontal line of the ‘口’ is slightly higher than the straight bar in ‘力’, which lifts up the character as a whole. The left side stroke in ‘力’ is shorter than the longer hook, a feature which is not necessary in the single ‘力’ character (Fig. 2).

Although Xiao Lai is a handwriting style font, the characters are clearly printed, unlike calligraphic script. The thick, even strokes remind me of the fat, round tipped Crayola markers that kids use to colour in pictures during elementary school. There are not many sharp lines – the outer edges of ‘口’ are rounded, while the inner corners hold a rectangular shape, resulting in a soft and friendly feeling. As Xiao Lai has its origins in the Japanese Seto font, there is an evident cute, kawaii-style influence on the glyphs. In addition to its lovable quality, its high legibility makes it a font that I can see being used in children’s books, exchanging informal notes, and snack packaging.

Noto Serif Simplified Chinese Noto Serif SC is part of Google’s Noto fonts project, which is made up of over 100 fonts, started in 2012 with the goal of achieving “harmonious, aesthetic, and typographically correct global communication, in more than 1,000 languages and over 150 writing systems.” (Google Fonts 2022).

Because the Noto Chinese, Japanese, and Korean fonts were developed as a collaboration between Google and Adobe, they are also known as “Source Han” in Adobe’s Source font family. Following the release of their first East Asian typeface in 2014 – Source Han Sans (Noto Sans CJK), they released Source Han Serif (Noto Serif CJK) in 2017. Although both companies use different names for their typefaces, their East Asian fonts share the same glyphs, and support traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. On this project, Dr. Ken Lunde was the project architect and Ryoko Nishizuka was the chief type designer.

The font is classified as Song Ti in Adobe’s font library. Song is a writing style originating from the Song dynasty, using woodblock techniques during the development of the world’s first movable type. Defining characteristics of Song glyphs are the thin horizontal lines contrasting with thicker vertical strokes, and the triangle-like stroke endings, sometimes referred to as Chinese ‘serifs’ (Wong 2013). This makes the Chinese font a suitable companion for the Latin Source Serif from Adobe and Noto Serif from Google.

Although the glyphs have been standardized, there still remains a strong and traditional feeling. This, in part, is due to the lines that maintain aspects of calligraphic brush strokes. For example, the curved stroke on the left side of ‘力’, when written by hand, begins from the top and continues downwards. In the digital character, the gradual transition from thick to thin resembles that of a physical stroke. The hook on the bottom right of ‘力’ also reminds me of the resulting stroke when a brush suddenly makes a curve to the left, forming a small wave before it reduces in width. Further, the stroke endings are angled sharply, yet also have roundness. On the vertical lines of ‘口’, the starting point creates a straight diagonal tip, while the end is slightly curved (Fig. 3).

The combination of strokes both thick and thin, and angled and round, builds a striking tension and harmony among the characters. Noto Serif SC is a versatile font that can be used for headings and body copy in a variety of contexts, such as essays, newspapers, and online blogs. Sentences set in Noto Serif SC will be taken seriously and read with ease. It also works well in a bilingual context, as it has been designed to pair with both Source and Noto typefaces.

流江毛草 (Liu Jiang Mao Cao) 流江毛草 is a font from ZhongQi Fonts (钟齐字库), based on the calligraphy of Liu Zhengjiang. It is part of the open source Google Fonts project, and its first commit on Github was made in February 2019.

This style can be considered a cursive script, which originated in China during the period from the Han to Jin dynasties, as early as 202 BC (Qiu 2000). This calligraphy functioned as a shorthand to make Chinese writing faster, by merging or modifying strokes, typically with brush pens and ink on thin pieces of bamboo and wood (Leung 2008). As digital fonts started to be produced in the late 1960s, calligraphic Chinese fonts began to emerge in the late 1990s, after more practical fonts, such as Songti and Heiti, had already been in use.

The characters of Liu Jiang have a rough quality to them, that create a feeling of authenticity. At a glance, the strokes seem smooth, however, after a closer look, they appear to have an uneven, almost bumpy, texture, that resemble the shape of ink. The strokes are thicker in the starting points of writing, in which ink would be more abundant on the brush. By looking at the glyphs, it is clear where the writer lifted the brush, and where they applied more pressure (Fig. 4).

They look like they were painted in a hurry, which is the point of cursive script. When writing ‘加’ by hand, you would start on the left with ‘力’, making the first stroke from top to bottom. Next, you would make the curve that crosses through your first line, and end with a small hook. In Liu Jiang, the hook “accidentally” touches the vertical stroke, which would not occur if the characters were being printed slowly. ‘口’ is typically written in three strokes – first, the vertical line on the left, second, the upper horizontal line and the right vertical line, and third, the lower horizontal line. However, in cursive, ‘口’ is often written in one or two strokes instead. Thus, we see in ‘加’ that the lower line is not fully formed, and the shape of ‘口’ has not been closed. In the single representation of ‘口’, we see another way that this character is commonly written in cursive. Rather than lifting the brush to draw a separate lower line, the lower line is extended from the previous stroke.

As Liu Jiang is a calligraphic font, it carries a sense of tradition and art. The characters are rushed yet sophisticated, like a noble woman who holds up her long gown as she runs across dirt and grass. The movement of the brush strokes creates a rhythm and flow among the characters. However, these aspects of Liu Jiang may make text more difficult to understand for novice readers, and thus more suited for large sizes compared to body text. Liu Jiang looks graceful when used for headings on restaurant menus, poster titles, artworks, and logo designs.

References Cai, Qing, and Marc Brysbaert. “Subtlex-Ch: Chinese Word and Character Frequencies Based on Film Subtitles.” PLoS ONE, vol. 5, no. 6), 2010. “How Many Characters Are There?” BBC, BBC, 2014. Leung, Irene. “Writing and Technology in China.” Asia Society, August 2008. Lxgw. “Kose-Font: A Chinese Handwriting Font Derived from Setofont.” GitHub, 11 November 2022. “Noto: A Typeface for the World.” Google Fonts, Google. Sheng, Huadong. “加 - Dong Chinese Dictionary.” Chinese Character Wiki, 7 July 2019. “Source Han Serif.” Typekit, Adobe Systems Inc., 2017. Qiu, Xigui. Chinese Writing. Society for the Study of Early China, 2000. Wong, Jeremiah. “Fundamentals of Chinese Typography.” Jiromaiya, 4 January 2013. Yao, Max. “內海字體:瀨戶字體的繁體中文補字計畫.” Max的每一天, 2 March 2020. “加.” 漢語多功能字庫 Multi-Function Chinese Character Database, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 8 July 2014.